Yube Inu, Yube Shanu

Pueblo Garzón, UY

March 4th — March 27th, 2022

Daniel Revillion Dinato is an anthropologist and curator. He has worked with the collective MAHKU since 2016 and has already held two exhibitions with the collective: Turismo Exótico Espiritual [Exotic Spiritual Tourism] (2017) and Tudo é feliz. Tudo é Perigoso. Tudo é Divino, maravilhoso [Everything is happy. Everything is dangerous. Everything is divine, wonderful] (2021). He is currently a PhD candidate in Arts Studies and Practice at the University of Quebec in Montreal (UQAM), where he develops the concept and practice of curator-txai, a long-term curatorial practice with MAHKU.

In this exhibition, for the first time in Uruguay, MAHKU presents four paintings and 16 drawings of eight huni meka chants. The works, made by Pedro Mana, Acelino Tuin, Cleiber Bane, and Kássia Borges under Ibã's guidance, are accompanied by an audio recorded in 2017 in the Chico Curumim village during an ayahuasca ritual, in which we can hear several of these chants, passed down through generations by those responsible for chanting them during the ceremonies, the txana. Also included in the exhibition is a painting of the myth that gives the exhibition its name, Yube Inu, Yube Shanu, made by Edilene Sales, Ibã's daughter.

What myths belong to this place?

What myths belong to this place? Can you still hear them? Is it still possible to understand them? Ibã Huni Kuin, founder of MAHKU (Huni Kuin Artists Movement) and co-curator of this exhibition, says that myths are "inside us". They are, therefore, alive.

One of these living myths provides the name for this exhibition: Yube Inu, Yube Shanu. It is a central myth for the Huni Kuin, an indigenous people of about 13,000 habitants who live in the state of Acre (Brazil) and in Peru. It tells the story of a man, Yube Inu, who, while going hunting, comes across a curious scene: he sees a tapir throwing three jenipap fruit into a lake, from which comes out a beautiful boa constrictor, called Yube Shanu, with whom the tapir has a sexual relationship. That day, Yube Inu returns home intrigued, determined to repeat the tapir's action the next day. He wakes up early, tells his family that he will go hunting and, upon arriving at the lake, does the same as the tapir: he throws three genipap fruit into the water. From there, Yube Shanu appears again. She, the boa constrictor, says she will stay with him, only if he is not married. Yube Inu, enchanted, lies and goes with her to the underwater world of boa constrictors, where they live and have three children.

One day, Yube Inu observes his father-in-law preparing ayahuasca (called nixi pae by the Huni Kuin) and, curious, asks to try it. At first his wife denies it, but eventually gives in to her husband's pleas. When the “mirações” (the visions caused by the drink) begin to appear, Yube Inu realizes that, in fact, that family is not like him, they are all boa constrictor people. Frightened, he then decides to run away and return to his old family that he had abandoned. The bodó fish (Hypostomus plecostomus) helps him in this endeavor, carrying him back to the surface. Once there, he finally finds his original family and transmits the knowledge of how to prepare ayahuasca, as well as the chants that should be performed during its consumption—knowledge learned from the jiboias. His former boa-in-law, Yube Shanu and his boa children, however, do not give up on finding him again. One day, Yube Inu goes hunting near a river and is surprised by his former family members who hunt him down, carrying half his body back to the boa constrictor world. Yube Inu dies, but to this day he reappears during ayahuasca mirages in order to pass on the knowledge learned from the boa constrictors to the Huni Kuin.

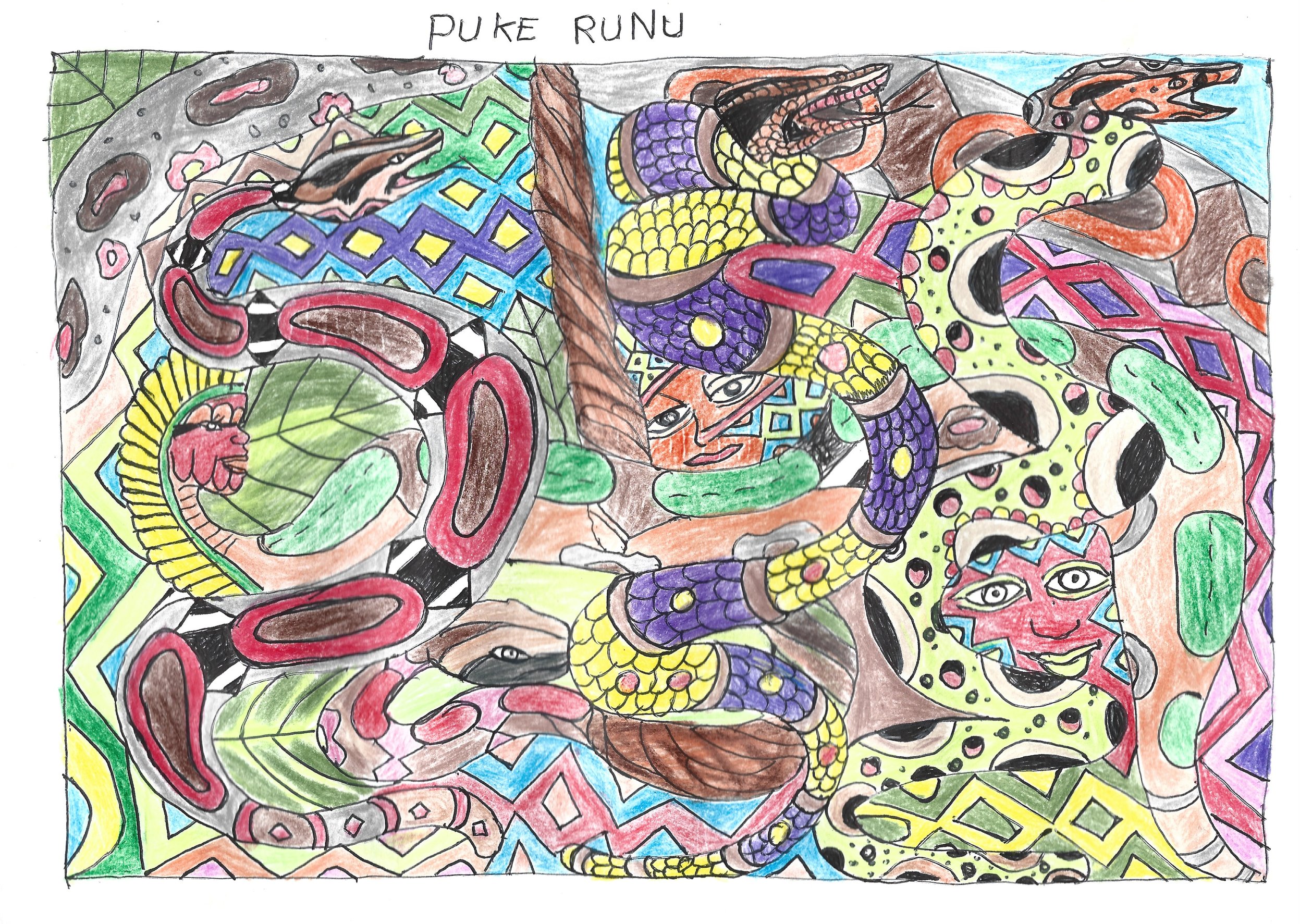

When Ibã finished telling me this myth, he said: Yube Inu date long ago. He is still going far, because he is alive. The MAHKU, like Yube Inu, also datego far. Their knowledge of the forest and of the nixi pae, or ayahuasca, make them cross worlds. More precisely, and the huni meka chants, enhance the rituals with nixi pae among the Huni Kuin. It is these chants that now bring MAHKU to the Piero Atchugarry Gallery in the city of Garzón, Uruguay. The members of MAHKU paint these chants, thus making them visible for those who hear but do not understand them. Therefore, we are speaking about a complex translation performed by the artists. The ayahuasca language, taught by the jiboias and spread by Yube Inu, is transformed into images by the artists, under the guidance of Ibã, who knows them best. The images are also transparencies of the mirages (visions) that the ayahuasca itself helps to produce. Consequently, there is a distributed authorship between human, non-human, and mythical

beings. MAHKU is a spirit, not a person, says Ibã. The resulting figurative images, called dami in the Hãtxa Kuin language, are sometimes merged with the traditional graphics of the Huni Kuin people, known as kene, and do not present a linear story, but are composed of a juxtaposition of images/events evoked by the chants and the visions.

Text by Daniel Dinato

Selected Works

Artists